History

The ISCFS Story

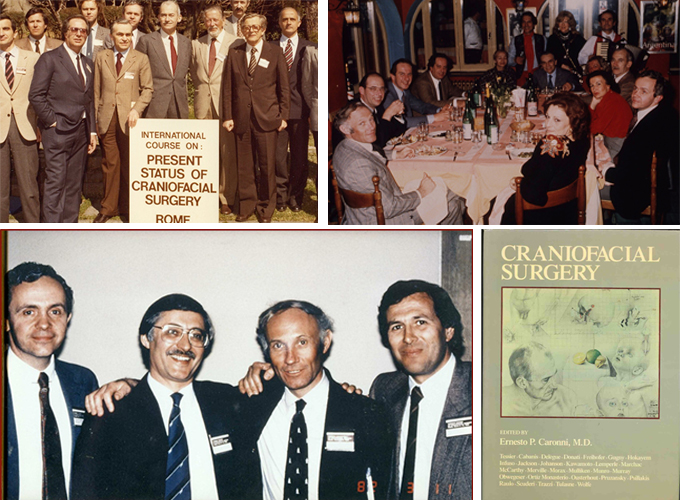

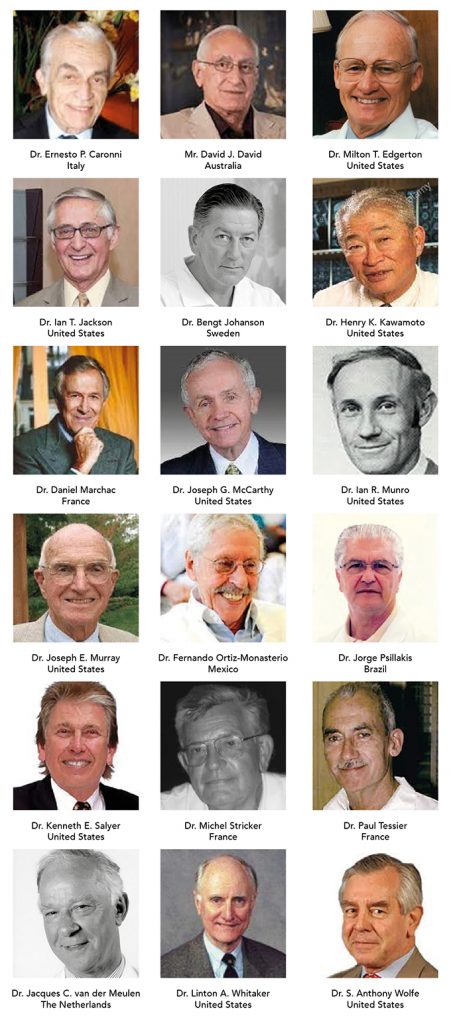

The International Society of Craniofacial Surgery (ISCFS) was founded in June of 1983 in Montreal, Quebec, Canada as the Craniofacial Chapter of the International Confederation for Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery (IPRAS). The eighteen founding members represented the leading plastic surgeons in the world with an interest in and focus on craniofacial surgery. Initially named the International Society of Craniomaxillofacial Surgery, the organization renamed itself as the International Society of Craniofacial Surgery thus more accurately reflecting the work of the membership and to acknowledge the divergence of the fields.

The ISCFS motto Pourquoi Pas?, or Why not?, summarizes the innovative spirit of the field of Craniofacial Surgery and pays homage to two of its pioneers. Paul Tessier, when once faced with a difficult case of teleorbitism, asked Gérard Guiot, his neurosurgery colleague, whether an intracranial frontal approach to midface was possible. After a brief pause, Gérard Guiot replied, pourquoi pas? This combination of innovation and surgical conviction led to the birth of the specialty.

Paul Louis Tessier was born at Heric on the Atlantic coast of France, near Nantes.

Tessier joined the pediatric surgery service at St Joseph in November 1944. The chief was Georges Huc who, although basically a pediatric orthopedist, was a friend of Veau and treated cleft lip and palate and hands. He was to have a great influence on Tessier who regarded him as a calm, good surgeon, a true gentleman, and father figure.

Paul Tessier Story (->click here for more)

After the liberation of Paris, the Red Cross Unit was transferred to Hôpital de Puteaux then to Hôpital Foch in March 1946. Tessier went with Virenque, where they were joined by a second maxillofacial team led by Ginestet, a professional soldier from Lyon. The two chiefs became arch enemies and ran their services completely independently. At about the same time Tessier began spending a month or two in England twice each year with Gillies, McIndoe, Mowlem and Kilner where he learned many new ideas (‘it was a revelation’) and developed a fondness for this country. The ‘Marshall plan’ provided him with an opportunity to visit the United States. In New York he saw many of the leading American plastic surgeons of the day including Aufricht, Converse, Connley, Bunnell, Boyes, Brown, Byars and others.

Paul Tessier Story (->click here for more)

In 1957 a young man consulted Tessier about a facial deformity, the like of which he had never previously encountered. He was described as having ‘prodigious exorbitism with a monstrous aspect’. When Tessier saw him again two months later, having carried out some research, he knew that the deformities were the result of Crouzon Syndrome and decided that the maxillary, orbital and facial deformities should be corrected in one operation.

After a lot of research & commitment from Tessier, practicing the operation on dry skulls and cadavers, the patient was finally operated on, the facial skeleton being completely freed from the cranium and advanced by 25 mm via multiple facial incisions. Bone grafts supported the advanced skeleton, but despite all the planning, the bony defects were much larger and more irregular than had been predicted. As a consequence, fixation became a major problem and after two weeks the patient’s face remained loose. Finally, an effective external fixator was constructed (not at the first attempt) and a stable result was achieved.

Tessier and renowned neurosurgeon Gerard Guiot carried out their first complete reconstruction.

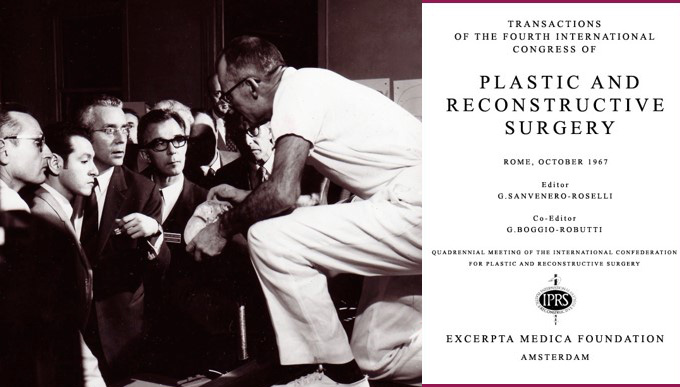

The field of craniomaxillofacial surgery was born after a long gestation period, and it was not until Tessier presented his work at the International Congress of Plastic Surgery in Rome in 1967 when he realized that it really was something new. Such was the interest generated that he organized a meeting at Hôpital Foch later the same year to which he invited a number of distinguished plastic surgeons, maxillofacial surgeons, neurosurgeons, ophthalmologists and pediatricians. Over a period of one week, he presented all the patients on whom he had operated and carried out four further procedures, two hypertelorism corrections and two facial corrections for Crouzon Syndrome, for their critical review. At the meeting’s end, he provoked a discussion to see whether the assembled clinicians felt it reasonable to continue the surgery or not in view of the inherent risks. Fortunately, they gave their support.

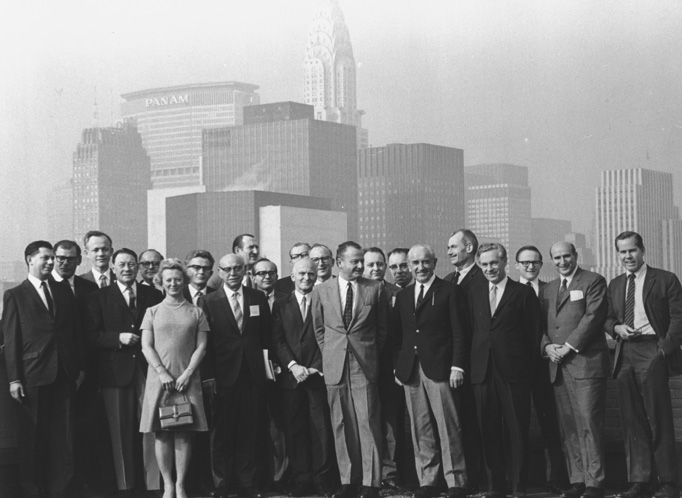

New York University

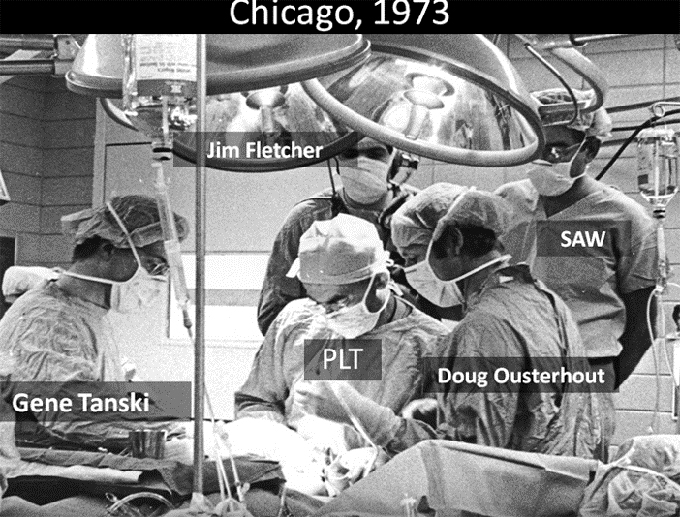

Chicago

Chicago

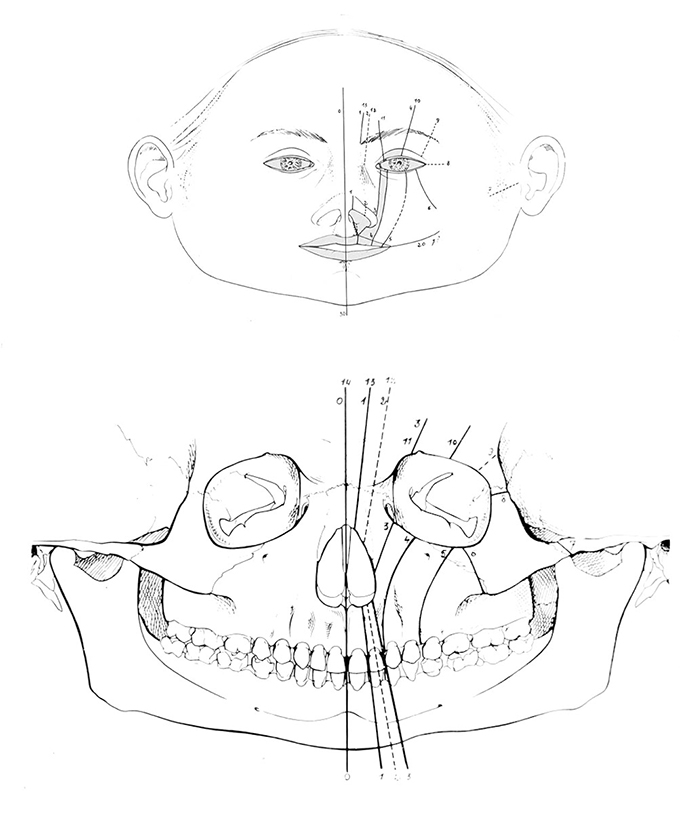

Tessier Classification

New York University

Rome – A Key Meeting

The International Society of Craniofacial Surgery (ISCFS) was founded in June of 1983 in Montreal, Quebec, Canada by 18 founding members (see photos) as the Craniofacial Chapter of the International Confederation for Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery (IPRAS).

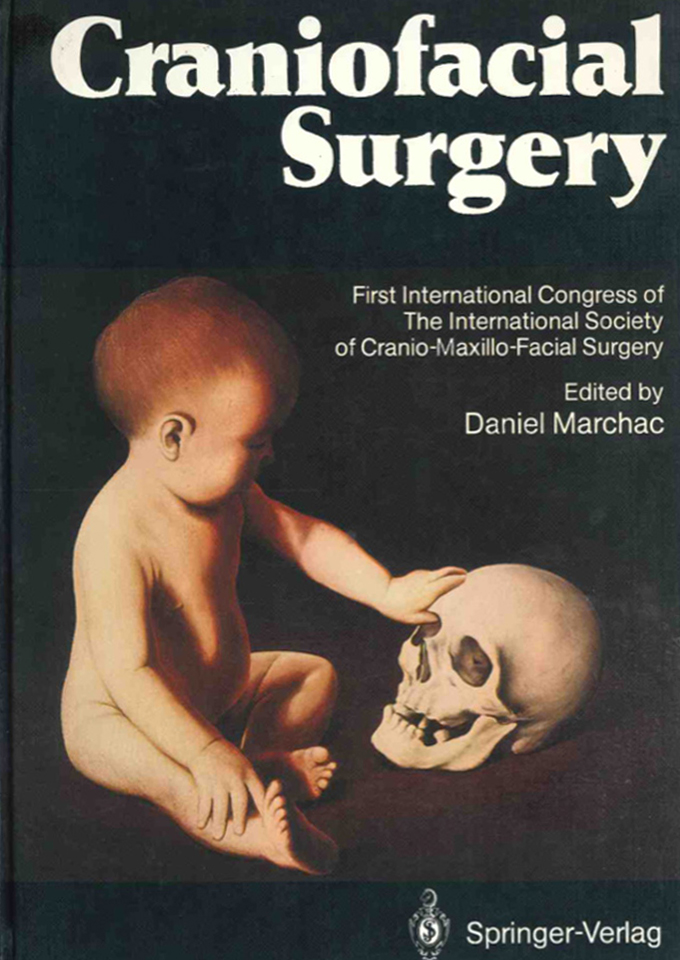

The Society’s first meeting was held in La Napoule, France, with Dr. Paul Tessier presiding as honorary President.

“THIS FIRST MEETING NOW BELONGS TO THE HISTORY OF OUR SPECIALTY, AS DOES THE COURSE ORGANIZED BY E. CARONNI IN ROME (MARCH, 1982).”

The meeting was held in New Dehli, India, at the time of the International Confederation meeting, Dr. Paul Tessier presiding. It is known as “the forgotten meeting” as many attendees fell ill.

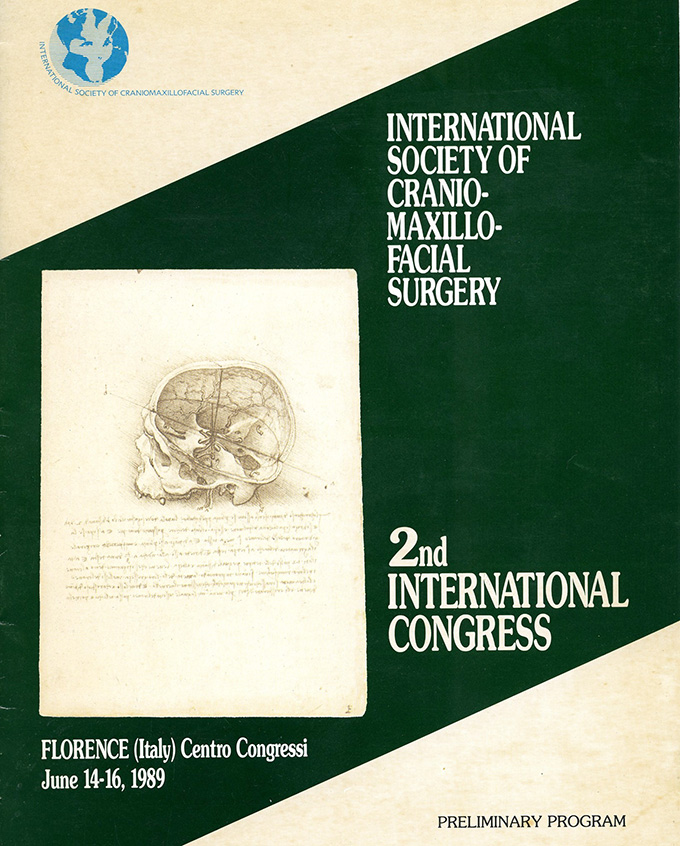

The meeting was held in Florence, Italy, with Ian Munro presiding.

The meeting took place in Santiago de Compostela, Spain, following the International Confederation Meeting, with Dr. Joseph McCarthy as president.

At this meeting, Tessier inaugurated the first Tessier Lecture.

Fernando Ortiz-Monasterio presided over the meeting in Oaxaca, Mexico. This year, the society changed its name from International Society of Cranio-Maxillo-Facial Surgery to International Society of Craniofacial Surgery.

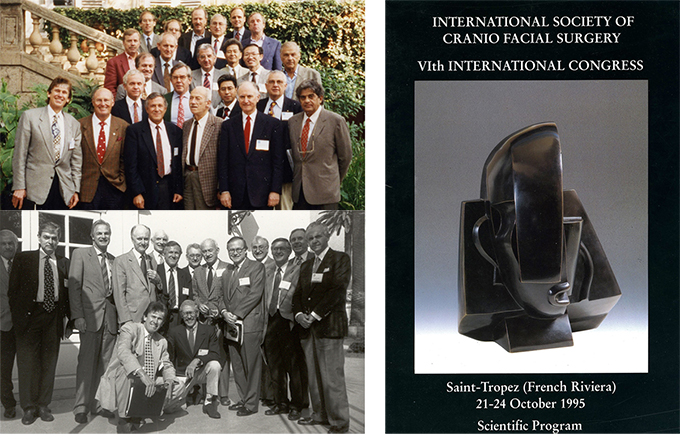

This year the meeting took place in St. Tropez, France, under Daniel Marchac, with surgeons attending from 29 countries!

It was the first time that the society met in the United States – in Santa Fe, New Mexico – with Linton A. Whitaker as President. The seventh biennial Congress was attended by more registrants than were present at the previous meeting.

8th Biennial Congress in Taipei, Taiwan.

Paul Tessier receives the Jacobson Prize, American College of Surgeons in Chicago.

The first meeting of the new century took place in the Baltics, in Visby, Gotland, Sweden.

After Twenty years, the founders once again came together in Monterrey, California.

In December, Paul Tessier is awarded the “Lègion d’Honneur” in Paris.

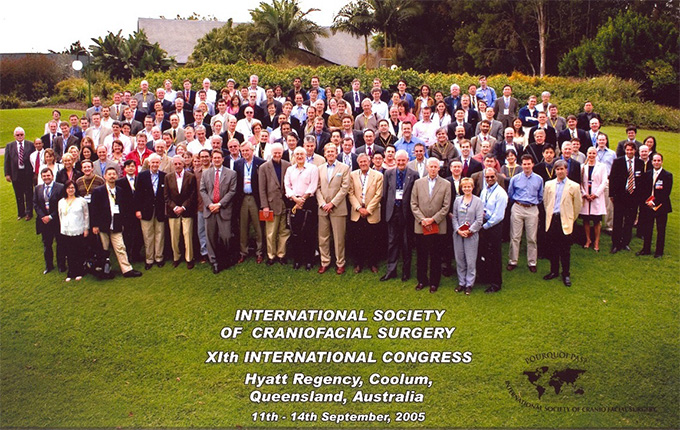

At the Congress in Coolum, Australia, the Tessier Medal was awarded to for the first time – to Fernando Ortiz-Monasterio.

In June of this year, the funeral service for Paul Tessier in Val de Grace is held.

The Ortiz-Monasterio Lecture was inaugurated at the Congress held in Jackson Hole, Wyoming.

This year the Daniel Marchac Award is given the first time.

18th International Congress in Paris, France

19th International Congress as a virtual congress

20th International Congress in Seattle, WA, United States

Start of the quarterly ISCFS Webinars

Start of quarterly ISCFS Newsletter

Start of Fellowship Directory on Website